From Caves to Cubes: A History of Mapping

The Early Days

Before the term video mapping existed, humans were already mapping the world through light and surface.

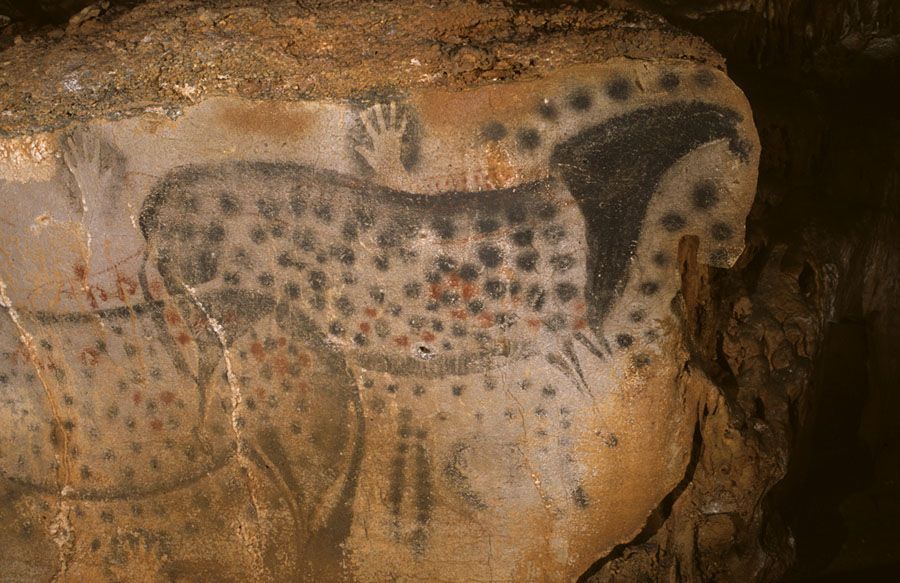

In the depths of the Grotte de Lascaux, Chauvet and Pech Merle in France, the first image-makers discovered that the irregular shapes of the cave walls could become part of the image itself.

The convex curves of rock became the flanks of a bison, the shadow of a torch made an animal appear to move.

These early artists weren't just painting; they were mapping — using the architecture of the world as a canvas, embedding illusion within matter.

The rock surface was not neutral background but a collaborator, a primitive topology for representation.

The renaissance

Centuries later, this same dialogue between image and space found new expression in the Renaissance.

The discovery of linear perspective by Brunelleschi and Alberti was, in essence, a mathematical form of mapping — a way to project three-dimensional reality onto a two-dimensional plane.

Artists like Pere Borrell del Caso, with his 1874 painting Escaping Criticism, pushed the illusion to its paradoxical limit: the figure literally steps out of the frame. The painted world invades the viewer’s world.

The image reclaims space. This is the spirit of trompe-l’œil — a trick of the eye that anticipates every future experiment where image and reality blur.

By the Baroque era, illusion expanded beyond the canvas to encompass whole architectures. The frescoes of Andrea Pozzo at Sant’Ignazio in Rome transformed ceilings into infinite heavens, merging painting, perspective, and built space.

Churches became immersive environments — proto-domes of projection — where light and geometry conspired to suspend disbelief.

The human eye was now inside the image.

The Projector

With the twentieth century came the dematerialization of image and matter.

The paintbrush gave way to the projector. French architect and artist Hans Walter Müller, beginning in the 1960s, developed inflatable architectures and projected diapositives onto their translucent membranes, sometimes inside natural caves, calling these "topoprojections".

His environments breathed, expanded, and glowed — living architectures of light. Müller’s work fused the ephemeral and the structural, prefiguring the “mapped” light architectures that would come decades later.

In the 1980s, American artist Michael Naimark introduced a crucial shift: the feedback loop between real space and projected image.

In his project Displacements (1980–84), he filmed a domestic scene using a rotating camera, then projected the same footage back into the same space using a rotating projector. The result was uncanny — a ghost of the recorded world haunting its original location.

Time, memory, and perspective were mapped together. Here the image no longer represents space; it inhabits it.

Naimark’s moving projection becomes a spatial event — a living cartography of perception.

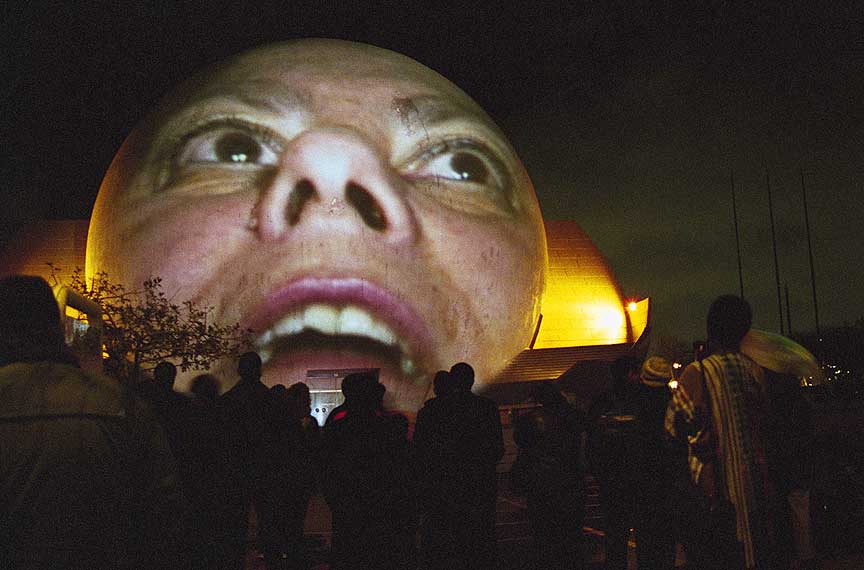

Parallel explorations emerged in experimental cinema and performance art: Krzysztof Wodiczko projected faces of marginalized voices onto urban monuments, politicizing architecture through illumination.

His works redefined the relationship between body, space, and image — each was a step toward mapping as a live, spatial, and social practice.

The Digital Age

By the 2000s, this lineage converged in the rise of video mapping, as digital technology enabled real-time alignment of image and architecture.

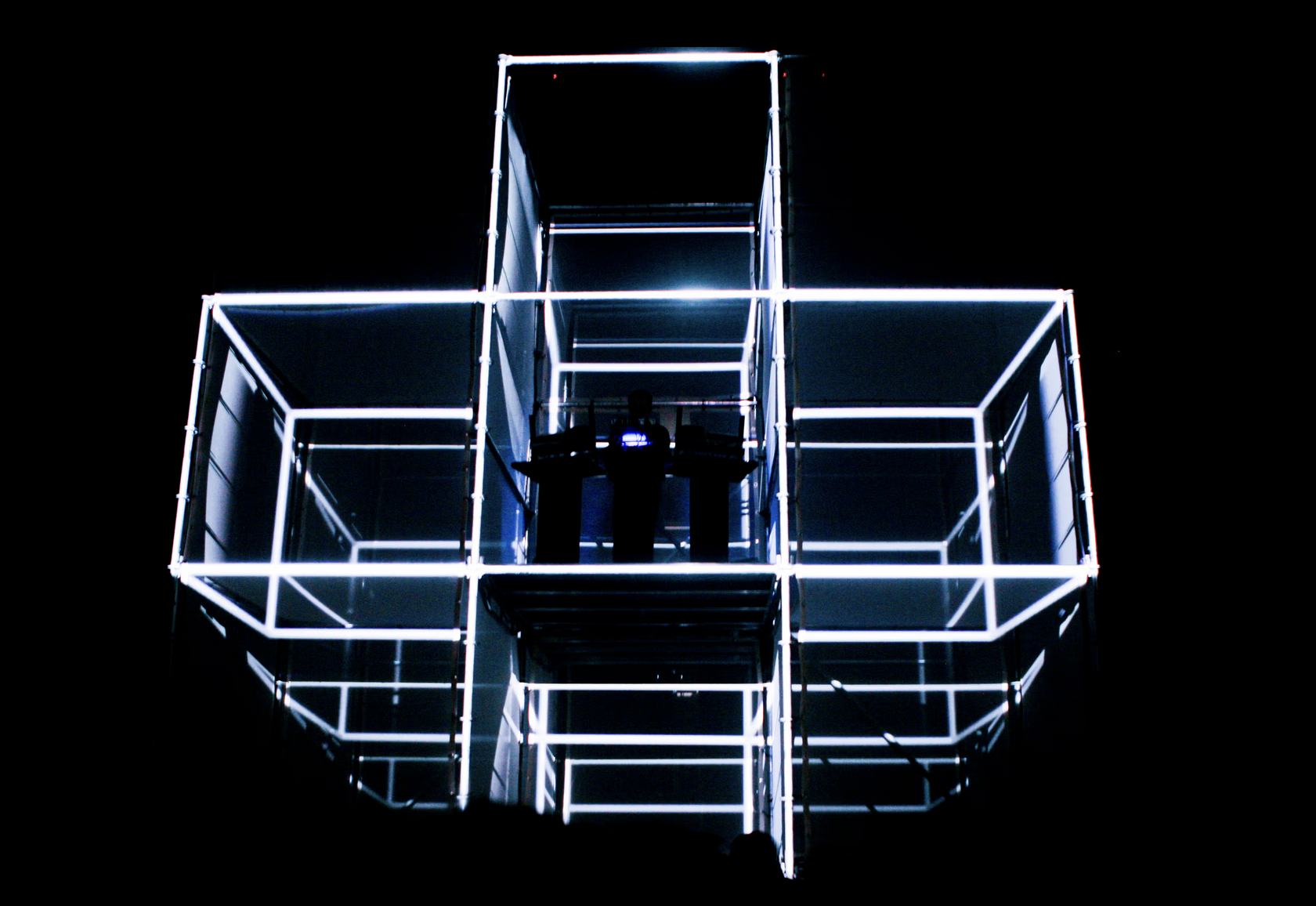

The artist collective EXYZT, later evolving into 1024 Architecture, translated this long history of illusion into the language of pixels, code, and stage performance.

In Étienne de Crécy’s “Beats and Cubes” live shows (2007), they constructed a luminous cubic structure whose geometry was mapped with video and synchronized with electronic sound. The cube pulsed, folded, and unfolded in sync with the beat — architecture became instrument, façade became choreography.

The legacy of Lascaux’s shadows returned, now algorithmically controlled, projected on modular space instead of stone.

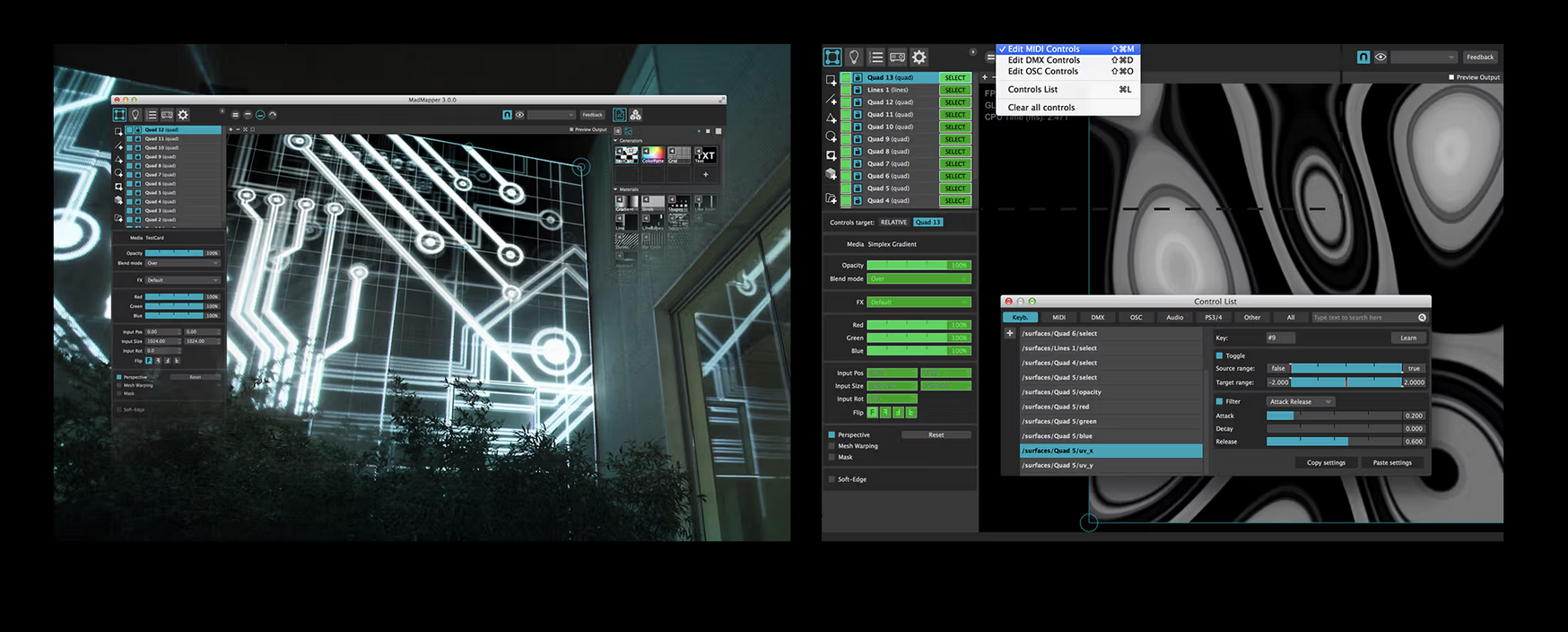

From 2010 onward, the story of mapping entered a new chapter with the creation of MadMapper, a software developed by artists, for artists.

Conceived by the Geneva-based studio GarageCube (creators of Modul8) in collaboration with 1024 Architecture, MadMapper distilled the complex craft of projection alignment into an intuitive visual interface.

What had once required specialized engineering became a fluid act of creation — drawing with light in real space.

This tool opened the field to a generation of designers, musicians, VJs, and visual artists, transforming mapping from an experimental niche into a widespread artistic language.

Like the pigments of Lascaux or the perspective grids of the Renaissance, MadMapper became the new brush of its era — a technology that democratized illusion, empowering anyone to sculpt space with light.

A Software for Artists

From 2010 onward, the story of mapping entered a new chapter with the creation of MadMapper, a software developed by artists, for artists. Conceived by GarageCube in collaboration with 1024 Architecture, MadMapper distilled the complex craft of projection alignment into an intuitive visual interface. What had once required specialized engineering became a fluid act of creation — drawing with light in real space. This tool opened the field to a generation of designers, musicians, VJs, and visual artists, transforming mapping from an experimental niche into a widespread artistic language. Like the pigments of Lascaux or the perspective grids of the Renaissance, MadMapper became the new brush of its era — a technology that democratized illusion, empowering anyone to sculpt space with light.

Today, mapping is no longer an illusion of depth on a surface — it is a method of composing reality itself.

From painted caves to digital architectures, each epoch redefined the link between image and world, light and structure.

The gesture remains the same: to reveal the hidden space between matter and vision, between seeing and being seen.

As the beam of a projector finds its surface, we are still in the cave, tracing the contours of the world with light.